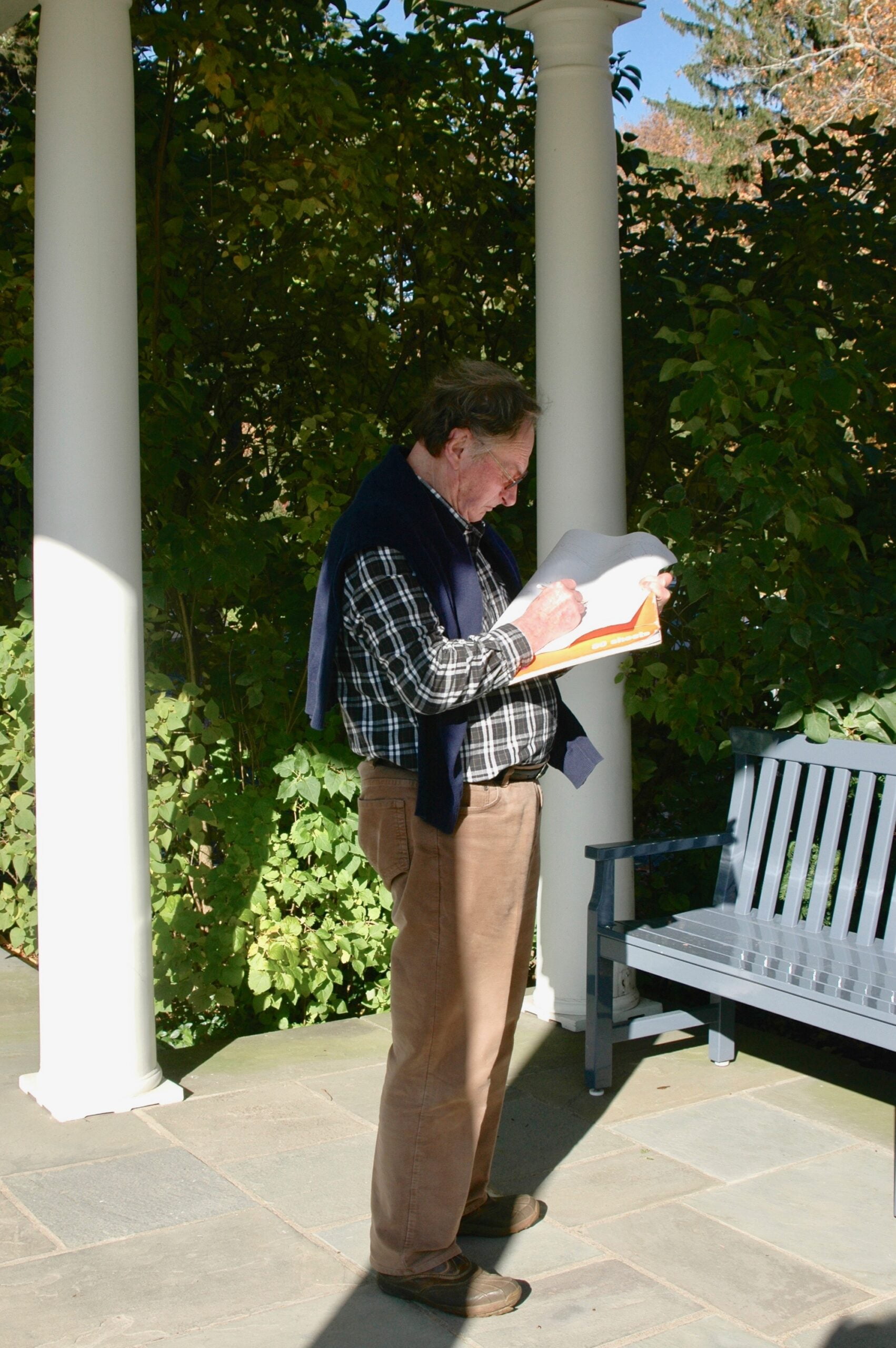

John sketching on site in New York State.

“Before setting pencil to paper … I like to discover as much about the owners of the site as possible: their likes and dislikes, what they intend the garden for – a place for the dogs, for entertaining in, or just to look at. I also like to see the inside of their house, to get some idea of their taste: whether elegant, sophisticated, or just plain pretty.

With this information in mind, I look at the site, its neighbours, and its views… It seems to me to be important at this stage to think of looking at the garden from inside the house and to try to integrate the design and colours into the garden design. A view from a window can be compelling even in the finest interior, which I see as the frame to the site….”

John Brookes MBE

1963, House and Garden

John Brookes MBE designed thousands of gardens over his nearly 60-year career including small urban courtyards, suburban gardens, large country estates and various public commissions. Dubbed “the man who made the modern garden”, John dramatically changed British garden design, making designed gardens accessible to people of all income brackets and demonstrating that gardens can and should be integrated as outdoor living spaces with the houses they surround. Above all, gardens should serve the desires and lifestyles of those who use them.

There is no such thing as a “John Brookes” garden because each garden he designed, whether in Britain or abroad, was uniquely tailored to site and client. The speed at which he worked was amazing. He was able to very quickly link architecture, garden, and the landscape and produce a unique design to the client’s style and preferences. In this exhibition we present four gardens on four continents that John designed to demonstrate how he connected each to its setting.

“…traveling and designing gardens beyond the British Isles….has taught me to dig a little deeper as well, beyond the style and needs of my client and into the cultural background of the job – as well as its physical backdrop and ambience of the place.”

Never one to shy away from new materials, locations, or trends, the design principles he applied were always consistent with the emphasis on proportion, form, texture, function, and pattern. As he travelled and worked abroad, he knew that each site had its own unique attributes: “The climate and the soil and the land formations are different; there is native vegetation and a local tradition of working the land or practising forestry management. A vernacular peculiar to that place becomes apparent, especially the buildings …how they are sited and in what kind of architectural style they are built…”

For John, connecting a garden to the local vernacular was essential. It was important because it made the garden feel at home in the surrounding landscape and reinforced a sense of place.

As his career progressed, he explained that “I’m increasingly more and more interested in the garden in its setting, i.e., letting the setting define elements of the design of the garden … and in the relationship between the environment and the man-made space … I’m interested in native plantings and regional distinctiveness. Otherwise with television you know all gardens will look the same if we’re not careful…It seems to me as some things become more universal other things should become more and more regional and local in order that we preserve our own unique flavour. And I am always interested in expressing that in garden terms…I try and focus on what I call “regional identity”.

With each garden, John’s overall objective was very simple: “Plants and climate may differ, and of course they need to be considered but I focus on what everyone wants: A garden that fits in with their lifestyle and which they can enjoy all year round. Delving into a culture and the vernacular of the landscape and working with, rather than for, a client to achieve what works for their needs gives each job the resonance that I really enjoy.” This was one of the many lessons he taught designers, homeowners, and contractors around the globe.

The four gardens presented in this exhibition demonstrate how John applied his design principles and philosophy to create unique gardens specific to site and client. On different continents, they are contemporary gardens with that sense of regional identity he valued. As with all his gardens, he evaluated the potential of the site – its views, its limitations, its topography, etc – and took on board the clients’ needs, styles, preferences, and the site’s regional identity before beginning his design process. Each of these projects took several years to complete. The last one, in Russia, was nearly completed when he passed away.

John replaced the narrow, steep stairs on the terrace early on, creating graceful steps wide enough for large pots of flowers.

The New York Estate is north of Manhattan, with views of valleys, hills, and the Berkshire Mountains. A 400+ acre property, the site includes formal grounds, paddocks, orchards, woodlands, and vast tracts of lawn. The main house stands atop a hill beside a large grey stucco guest house, and outbuildings, some grey stucco and others rustic, are dotted about nearby. The scale of this property had proven difficult for previous designers resulting in a disconnected set of features that blocked views, were too small, or felt contrived. The owner wanted a designer who could create a sense of fluidity, beauty, and proportion that felt comfortable in the landscape. His retreat from hectic city life, he wanted to be able to walk, ride, read, and entertain guests.

These modern Adirondack chairs are placed at the top of the orchard, overlooking a paddock of wild mustangs.

Though the interior of the client’s home was decorated in an elegant country style reflecting his interests and travels and was filled with pots of fragrant flowers grown in the client’s greenhouse, the interior was unconnected to the surrounding garden both visually and in style. John felt that the property’s dominant attribute was its views, both within the property and without. Some of those views were accessible from the main house and others from the gardens, seating areas, and walks John created.

John collaborated with Anthony Archer-Wills on a series of ponds, streams, and waterfalls to provide sound, attract wildlife, and a non-ending play of reflected light.

John opened and created views as he developed a series of formal gardens and a parkland around the house. He even moved nearly a swathe of a hundred apple trees from the interior of the orchard to create a view from a new seating area above it. The seating area featured modern Adirondack chairs and had views of a paddock featuring wild horses and the mountains beyond. He linked a giant, new Alitex greenhouse complex with a new potager that was visible from walks leading to the main house. With Anthony Archer-Wills he designed waterfalls and lakes adding sound, wildlife, reflected light, and a sense of remoteness. Using the spoil from the lakes he created sound barriers along nearby roads and thus a sense of enclosure. He linked all these spaces with a series of rustic walks.

The materials he sourced, the furniture he chose, the sculpture he found, the structures he built, and the plants he used were related to what was on site, tying the new features to the local vernacular.

Chopin, one of John’s favourite composers, once played at this stunning Polish estate.

The 19th Century Palazzo in Poland is a 2-3 hour drive from Warsaw. As he rode to the new site John took in the Polish countryside – cultivated fields, farm workers, villages, and numerous small religious shrines – gaining a sense of the bucolic, peaceful landscape that might surround his clients’ house.

He revised his preconceptions, however, when he arrived at a light-yellow stucco mansion with a formal circular driveway and formal grounds. The house, which had been built for minor royalty in the 1800’s before being used by Nazis and then as a multi-family dwelling during the Soviet years, had been restored by the new owner. John felt it was very “French” and so incorporated French influence in his design of the grounds – “a bit Empress Josephine”, as he described it.

The pavilion above the cascade matches several others in the formal gardens John created.

The gardens were primarily lawns with big trees that John felt created too much shade. There was a small lake above which the client wanted a cascade and a church spire in the local village was visible from the house, giving the property a sense of belonging to the Polish countryside in spite of its French feel.

John designed a terrace linked to the dining room and kitchen to exploit the view of the church spire and sunsets. Another terrace was built on the flat roof covering an indoor swimming pool. It masked the building in which the pool was built and allowed for a stunning seating area with views of the new willow-enclosed cascade he built above the lake.

John’s formal gardens with flowers, pergolas, and water features are spacious and bold.

John created formal flower gardens punctuated with pergolas and French style pavilions and defined by low walls of yellow stucco to match the house. An identical pavilion was built at the top of the cascade and provided a year-round focal point from various windows in the house.

John also developed walks through the woodland. The formal gardens and woodlands have various features and views contributing to a sense of place and always referring back to the formality and style of the house.

Note: We would like to thank Dr. Barbara Simms, author of “John Brookes Garden and Landscape Designer”, for kindly permitting the use of her images.

In Patagonia, John met the challenges of vast natural landscape with strong lines and simplicity.

A Bold, Contemporary Garden in Patagonia was John’s largest project in South America. John fell in love with South American in the 1990’s when he was working and teaching first in Chile, then Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil. The property in Patagonia is set in a larger-than-life, rugged landscape dominated by the snow-covered Andes Mountains and the vast Nahuel Huapi Lake. From the beginning John knew that the placement of the house and the design of the gardens would have to be determined by these views.

A beautiful infinity pool links the site to the massive lake beyond.

The house was still under construction and much of the lot was still undeveloped when John arrived, but he immediately set about determining what views would be visible from the various as-yet unbuilt windows indicated by the architects’ plans. He went on to identify areas of trees and scrub that needed clearing to open views and to identify where the essential outdoor entertaining areas should be. He knew and loved how important those outdoors areas are to the Argentine lifestyle and he designed a large entertainment space with a pool overlooking the lake, a pergola-covered sitting area, and a barbecue terrace constructed of timber and granite. The dining area was beside the pool where he placed ample loungers for sunbathers.

The strong lines of the terrace reflect the lines of the Andes, and the soft plantings relate to the adjacent wilderness.

The site’s topography was steep and uneven giving John the opportunity to exploit views from different levels within the garden which he connected to one another with wide flights of shingle steps. He also created a “great sweeping drive” leading to the front door. The drive included a rustic timber “rumble bridge” that spanned one of the two ponds he built on the side of the house opposite the lake. Finally, he created a children’s play area for the client’s small children.

In order to link the garden to the site and house, John used indigenous materials. Ever averse to squiggly, mushy lines, John relied on very bold and simple lines to connect the garden terraces to the view of the distant Andes using strong shapes that mirror the silhouette of the mountains. He used the ponds and the swimming pool to connect the site to the lake. His choice of plant material was simple and boldly grouped in masses that were large enough to “read” against the dramatic landscape.

John used plantings, curves, and earth shaping to provide privacy for this elegant dacha.

The Private Family Compound on a Russian River lies hours outside of St. Petersburg. The land is generally flat and is surrounded by pine woods, one of the few evergreens that survive in the region’s harsh climate. John’s client was developing a complex of modern wooden dachas to in which to house his mother, his staff, himself, and the security detail. The challenge of this property was to connect the dachas but providing privacy among them. He also had to balance screening the grounds from neighbours with opening views of the river.

The client’s mother would be in residence year round and wanted a garden in which she could grow fruit and vegetables while the dacha served as a seasonal country home to which the client could retreat from city life. John designed a small orchard, sitting area, vegetable garden and Alitex conservatory for “Mother”. He built a small lake with an island outside her dacha to provide her with a sense of space and year-round views.

The spoil from the ponds was hand shaped in undulating mounds to create a sense of intimacy within the property.

He used the spoil from this lake and the other water features he created to build small hills on the property’s perimeter and between the dachas to create a sense of seclusion. As machinery was too costly to bring to the site, a team of Gambian workmen were employed to do, by hand, the massive amount of earth shaping John required.

The site’s revised topography helped to emphasize the views of the river and John created a lawn sweeping down to its banks and an outdoor entertainment area where meals can be served, and the beauty of the water and sunsets can be enjoyed on the long, warm Russian summer evenings – the White Nights he himself so loved.

A lawn sweeps down to the river and a rustic but elegant dining and seating area.

The planting of these gardens presented challenges because few plants and shrubs are hardy that far north and plant material had to be brought in from Germany. The site was surrounded by “endless pine trees and silver birches” so John added sweeps of Annabelle hydrangea, rugosa roses, and other hard plants that can take severe weather and contrast well with a dark evergreen background.

This was John’s last project. He made his final visit to the site in September of 2017, just six months before he died.

“It is to the form of the landscape, or of a garden, that one instinctively reacts, and the interesting questions are: how much do you impose upon that form and what do you build it with?

These fundamentals never change: to create a perfect union between structure and architecture – the verticality of the buildings on the site and the horizontality of the design solution and its subsequent planting. Planting is the least important aspect …”

John Brookes MBE, A Landscape Legacy,